THESEUS-ARCHIV

Zeichnung #23 aus dem Theseus-Archiv, entstanden im Rahmen der Workshops für die Faculty mit Mitgliedern des Chors der documenta 14 in Kassel und Athen

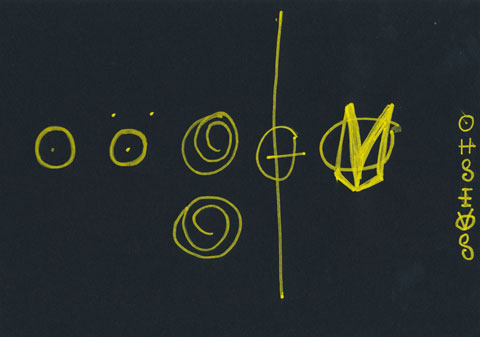

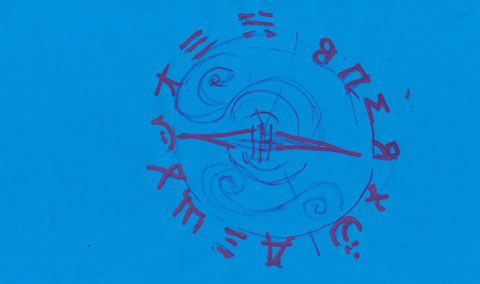

Drawing #101 & #8 from the Theseus-Archive, created by members of documenta 14 Chorus at Athens and Kassel in the context of my workshops for the Faculty of documenta 14

Workshop with members of the documenta 14 Chorus at Fridericianum in Kassel, view from above © Filmstill Anton Kats

Workshop with members of the documenta 14 Chorus at Fridericianum in Kassel, view from above © Filmstill Anton Kats

Drawing #85 from the Theseus-Archive, created by members of documenta 14 Chorus at Athens and Kassel in the context of my workshops for the Faculty of documenta 14

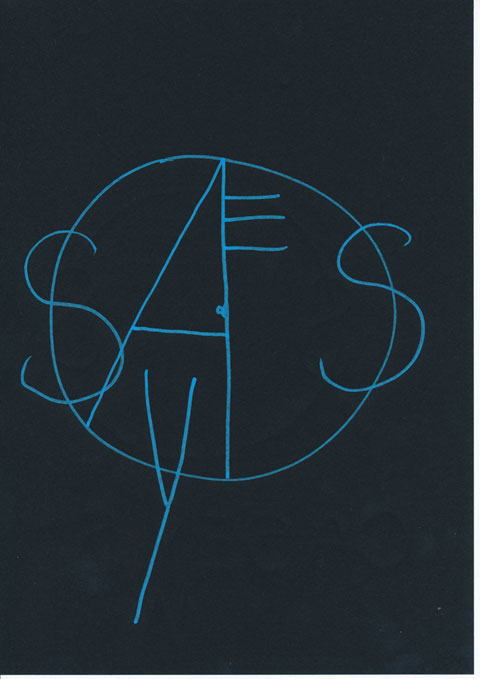

Drawing #141 from the Theseus-Archive, created by members of documenta 14 Chorus at Athens and Kassel in the context of my workshops for the Faculty of documenta 14

The Theseus-Archive consists of a constantly expanding archive of drawings that participants develop in my workshops in context of a text fragment from the 400th century BC. One of the aims of this collaborative work is gathering and sharing experience about the ways in which we can learn and teach. * This goes hand in hand with the investigation of forms of knowledge. What is ‘knowledge’, when do we know something, how can we pass on what we know?

I invite the participants for a graphic interpretation of text lines **, which I read out loud several times and at the same time make available visually as a projection on a wall. The result is a wide variety of drawings.

But what’s the text about? A person, telling about herself, that she is “not skilled in letters” describes six forms. The text originates from a fragment of the lost tragedy Theseus by Greek poet Euripides. Euripides lets a protagonist who can’t read, utter these words,. Standing on the shore of the sea, the person perceives a ship in the distance. On the ship she discovers signs, which she now describes to us, without understanding what they mean.

It is only in a exchange, in the overall view of the resulting drawings, that we come a little closer to the clandestine. And it gradually becomes apparent that Greek letters of the name “THESEUS” are described. In the group, a process of touching and feeling something, which occurred over thousands years ago opens up. There are many possible interpretations of this experience, which are reflected in the drawings. Linear thinking and the associated concept of knowledge seem artificial, subjective and context dependent constructions, which can also restrict one’s own perception, learning and teaching. Letters and writing are not self-evident.

This leads in a further step to the investigation of historical contexts of the development of the alphabet. Western European letters of the alphabet are based on the alphabet developed by the Greeks. For them, the discovery and development of signs for sounds was so central that they embodied the forms of the individual letters in performances by the choir.

As part of my workshop, we will first explore performative exercises. Among others, we stand in a circle and place a ball in the centre ***. Seen from above, we as a group form a large letter, which turns out to be the Greek letter Thìta: a circle with a dot in the centre. It forms the first letter of the Theseus fragment. So we have already physically experienced the form of this letter without it reaching our consciousness. Connecting the body experience with the reading, listening and drawing happens later and goes along with the presentation and discussion of the drawings.

I was able to first experience the concept for the Theseus-Archive in collaboration with the chorists of documenta14 in Athens and Kassel, the Faculty and Anton Kats. 160 members of the choir – the chorists – conducted walks for and with documenta 14 visitors. The development of the choir in the course of documenta 14 was conceived with the Faculty – a group of artists and art educators, who brought in different methods and approaches. Members of the faculty included Keiko Higashi, Gila Kolb, Konstanze Schütze, David Smeulders, Leanne Turvey and myself. See: http://www.documenta14.de/de/public-education/ [accessed: 31.03.2018]

* The participants of these workshops come from a variety of artistic fields, such as university lecturers, pedagogues or art(s)- and cultural educators as well as artists.

** I’m not skilled at letters but I will explain

the shapes and clear symbols to you.

There is a circle marked out as it were with

a compass and it has a clear sign in the middle.

The second one is first of all two strokes and

then another one keeping them apart in the middle.

The third is curly like a lock of hair

and the fourth is one line going straight up

and three crosswise ones attached to it.

The fifth is not easy to describe:

there are two strokes which run together

from separate points to one support.

And the last one is like the third.

—Euripides, Theseus 1

From: Hendrik Folkerts (2017): Keeping Score: Notation, Embodiment, and Liveness

1 Euripides quoted in Anne Carson, Eros the Bittersweet (London: Dalkey Archive Press, 1998), pp. 57–58.

*** First I invite the participants to non-verbal experiences in space. I ask them to position themselves in a circle, in which I am placing a ball in the centre. I incite to estimate the distance from each one’s self to the centre and then covering this distance closing the eyes. This could happen through walking, leaping, body twisting, crawling, rolling, backwards, forwards in order to touch the ball with an improvised spontaneous movement to bridge the space in between oneself and the centre. It is crucial to undergo this experience not seeing in order to experience the other senses as well as the space. There is no fixed order, structure or rhythm given. Those who do not feel like it – do not participate. Sometimes it happens that several people close their eyes at the same time and set off to touch the ball without noticing the others. Sometimes nothing happens for a longer time. There is always a quiet agreement between the group on when to start and when to stop.

I observe that this form of “silent agreement” occurs non-verbally and without eye contact. A transfer of knowledge (“It begins. It ends”) about physical and spatial experiences takes place. At the same time we experience collectively something on a different level, beyond a classic introductions: here perhaps a hesitation, there a lot of humour, sometimes determination or lightness, and so on. And, also individually, new experiences can take place in relation to the estimation and experiencing of space in between without technical support, exclusively through physical perception.

These perceptions and experiences with oneself and the group are supported by the detachment from one’s own evaluations and assumptions and the engagement with the experiment of “perceiving” and putting aside categorizations. These and also some other exercises – which we do standing in a circle, throwing a ball or placing the ball in the centre – form a big letter seen from above. The Greek letter Thìta: a circle with a dot in the middle. After various other experiments, e.g. with the interpretation of terms in gestures and choreographies, I start with the drawings in regards to Theseus-Archive.